Looking for Leonora / a turn to the Tarot. By Elaine Tam.

Have you tried Co-star? No. And that is how I came to download the application Co-star. “We use NASA data to paint a complete picture of the sky when and where you were born. Our AI uses this information to personalize your chart, horoscopes, and compatibility,” the loading page reads. Thousands of years of ancient, astrological knowledge are fed into Co-star’s algorithm, to provide users with daily mantras and snippets of advice through push notifications. Remarking upon our renewed interest in astrology, Co-Star’s CEO sounds uncannily like a robotic soothsayer too: “[t]he crux of feeling like a human is being able to talk about your reality,” she says. To each their individual path, but one cannot not help but mourn the lack of substance and grit about this technological quick-fix. The age-old existential quest for meaning seemed disembowelled, and duly emptied out.

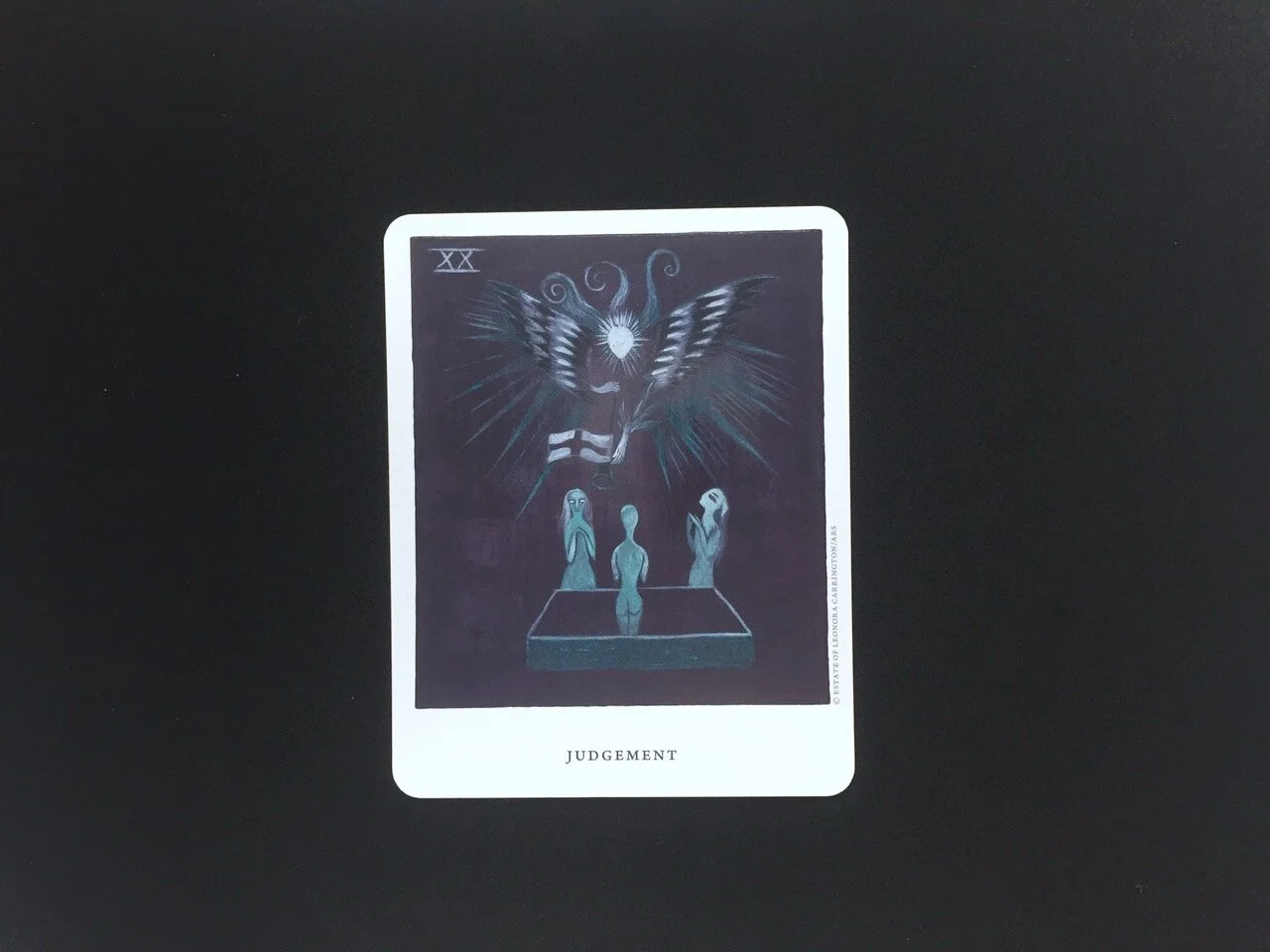

Co-Star notwithstanding, when I unwrapped my birthday present last year to read the words “Major Arcana” in gold lettering, I was confused, if not simply unprepared. In 2019, ‘mystical services’ was already a multi-billion-dollar industry, a head-spinning sum enough to arouse suspicion alone. Who, in the throes of existential desperation, was funnelling money out to this dubious market? Aloof curiosity aside, I had my private apprehensions. I had withstood so many growing pains, and wasn’t quite ready to fall into a tricksy bandwagon or risk regressing into a trend-tailing teen. My stars were jammed. But little did I know that it was in this small midnight blue box that I would go looking for Leonora, aided by the artist’s recovered suite of Tarot paintings turned Tarot cards.

Leonora Carrington is said to have rejected the Surrealist branding, be as it may that she had her fair flirtations with the group, she was content with its periphery. The notorious Max Ernst was smitten with her when they met circa 1937. She, the tender age of twenty; he, a tall drink of water, twenty-six years her senior. A smattering of photographs by Lee Miller show the pair at a group retreat in Cornwall, where one might (wishfully) speculate they engaged in esoteric activities of all sorts come sundown. For you see, The Moon is a card of madness and poetry. Your eye might latch onto the scorpion scuttling at the edge of the frame, a black gash splitting into the grisaille scene. It might dither on the twin canines, who in unison howl suprasensible calls. You might, like me, think of how the rain resembles tears, tears cut with the damp of a dark January’s day. In sifting through symbols to access the substrata of a reality, something inside us might emit the tiniest of cries, or appeal to our frustrated attention.

Sigmund Freud was allegedly baffled as to why the Surrealists had anointed him their ‘patron saint’. Fin de siècle was the time of Freud’s seminal The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), and a moment where psychoanalysis was vying for its legitimation as a scientific discipline. The Surrealists were likely refused by Freud for not complementing this agenda, yet still, they took to it like cats to cream. André Breton discovered The Interpretation while serving as a psychiatrist in a military hospital during WWI; it was there that he was confronted with the creative capriciousness of madmen who, castaways, were the discardable exploits of a ruthless war. Citing Freud passionately in his Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), he writes that realism flatters only the ‘lowest of tastes’, is a ‘dog’s life’, where the ‘dream finds itself reduced to mere parenthesis’. Further to an aesthetic and ideological movement, Surrealism was to be a countercultural refuge, enriching the lives of the glittering outliers adopted to its cast.

Following Breton’s manifesto, children are closer to a ‘true life’. It was around the same time that psychoanalyst Melanie Klein noted it is harder to detect schizophrenia in children, given how easily it is confused with the universally accepted notion of a child’s ‘wild imagination’. It is said that Carrington ‘saw things’ as a child... all manner of things. 1940 was the year of Carrington’s involuntary admittance to a sanatorium in Santander, on account of incurable insanity. With saudade for the Cornish sun, she had expelled Ernst, her ‘second father’, a complex affair which entailed her flight during his internment in France. Under duress, one particular hallucination arose wherein history, religion and nature were all within her — she contained them, as though she were the entire world. The World Tarot painting would then be the aquamarine heart of that very vision.

The World features a woman in its centre, encircled by a floating garland — a portal, a birth hole, which she dances gaily through. Here we have a swirling image capturing all sensitive life, invoking the joy of a pleasure-filled body and a soul that feasts on earthen delights. The World is a sensuous oneness that eclipses discrete forms of knowledge, the zenith of interconnectedness between all things. Visitor in the hours of despair, revelatory visions of this kind would foreground Carrington’s studies of astrological symbols, the Tarot, Mayan imagery and the spiritualism of Kabbalah and Buddhism. We shall never quite know if these visions were successfully wrung from her by the Cardiazol, or if she only ceased to speak of them with a fledgling’s freedom, choosing instead to safely bracket this period in fantastical novels. What we do know, however, is that they could be coaxed by a psychic automatism to take presence in her work. She would become their medium.

I learnt to conceive of Leonora Carrington by the tales of her use of hair. By this time, following the tumult 1942 onwards, she was settled in Mexico. Hair — half dead, half alive, the living deadpar excellence— featured in her omelettes, to the amusement and abjection of dinner guests. Loose cat fur would act as stuffing for the toys she would make and give to the children, the children who live truer lives. Eccentric though it may seem, her art and her life were engaged in a chiasmic fashion, a Möbius strip that likewise conjoins dream and reality. Hair bears all the hallmarks of a Surrealist motif; but also, one gives a lock of one’s hair to a lover. A hairline might recede but the dead can keep their hair. While glabrous flesh is fated to wither, hair will outlive you, the mummies in museums tell us so. Myth, like hair, can be spun around an index finger, and gives us something to hold onto. In 2011, the artist passed away and her life was given over to myth. Myth now seems to precede her, and she exists as this gorgeous excess.

Looking for Leonora was my question to her Tarot, the selection of cards that answered appear here as a guide to this text. The distant stars beget a possibility, a means of path, a field of virtualities. A splay of cards will call forth a reckoning — a game of image association meets a delightful play with chance. To it, we deploy intuitive practices commonly used in the reading of art, whereby we attune ourselves to symbols, colour, scale and proportion, compositional harmony… These are subliminal cues which coalesce as an instinct about the cards at hand. But the cards fall as they fall, and much like fortune or entropy, that is something we can neither learn nor choose. In this sense, there is a certain emergent co-creation between the deck and its player, insofar as one creates a non-hierarchical spread, which the other is moved to reflexively peel apart. Carl Jung’s notion of ‘synchronicity’ is perhaps best placed to describe what happens here: an acausal event convening with a hitherto covert inner state. It’s a sign! — a beauteous expression of ‘coincidences’ and their ‘chance concurrences’.

Art is a sort of magic that can discharge us from the psychic chokehold of reason, rationalism, realism... maybe even, in some small part, restore to us the ‘true life’ we relinquished in the haste to grow up. As Carrington once put it, art ‘comes from elsewhere’. It is, perhaps, the same verdant elsewhere that nurtures other realities to effloresce, and few have access to their secret being. But every so often, the stars may align. Something clicks into place. You find your gaze interlocked with someone else’s in the mirror.

References

Breton, André. ‘First Manifesto of Surrealism’. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Emre, Merve. "How Leonora Carrington Feminized Surrealism." The New Yorker. December 21, 2020. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/12/28/how-leonora-carrington-feminized-surrealism.

Jones, Allie. "Rising Signs." The Verge—CoStar. October 04, 2019. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.theverge.com/2019/10/4/20879631/co-star-astrology-app-zodiac-signs.

Jung, Carl, and R. F. C. Hull. Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Laity, Paul. "The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead – Review." The Guardian. April 05, 2017. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/05/the-surreal-life-of-leonora-carrington-joanna-moorhead-review.

Leddy, Siobhan. "Why Surrealist Leonora Carrington Envisioned Women as Wild Animals." Artsy. May 04, 2019. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-leonora-carrington-brought-wild-feminist-intensity-surrealist-painting.

McAdam, Jacob. "Tarot Card Meanings, Symbolism, Interpretation." 78 Nights of Tarot. July 03, 2017. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://78nightsoftarot.com/learn-tarot/tarot-card-meanings/.

Wullschläger, Jackie. "Analyse This: Freud, Dalí and the Surrealists." Subscribe to Read | Financial Times. January 11, 2019. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/f307b700-0e7c-11e9-a3aa-118c761d2745.