Life? or Theatre? (animated): a review of Charlotte, directed by Tahir Rana and Éric Warin

Like the proverbial hall of mirrors, Charlotte (2021), flashes before the viewer more images and questions than a single work of art can ever hope to resolve. In a mere hour and thirty minutes, the titular artist grows up, learns, lives, and dies, all whilst rapaciously artmaking amidst the backdrop of the second world war. The film, which takes its cue from Salomon’s semi-auto-biographical painted book, Life? or Theatre?, leaves the viewer acutely aware of the challenges that will have faced the filmmakers at every turn. Namely, how does one balance the need to create an animated film which is artistic and the pressure to represent the artist?

The urgency of this question is compounded by the fact that Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943), renowned painter and autodidact, remains comparatively little known among UK audiences (despite having been exhibited internationally throughout Europe and the US). Therefore, the animated film will be, for many viewers, their first encounter with the artist. Her story, however, feels not unusual; having been born and grown up in Berlin in the first part of the twentieth century, a member of a middle-class Jewish family, she died in Auschwitz aged 26. It is one of millions of such deeply sad stories that we cannot know of lives lost to the Nazis.

Whilst we cannot ignore her biography, the focus on her life story has tended to form a stumbling block to creatives engaging with her work on its own merit. As Griselda Pollock argues in Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory, 2018, in the many plays, operas and ballets which have considered her work, her paintings and her tragic status as a casualty of the holocaust have been collapsed. Despite Life? or Theatre? ending when Salomon hands it over to a local doctor for safe keeping, in fictional retellings, the curtain tends to come down at the point of Salomon’s death, seeming to suggest that the work is little more than didactic reportage.

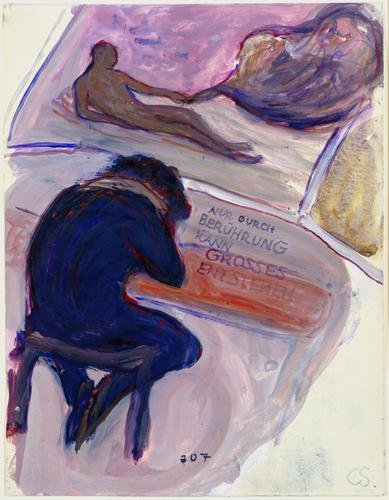

painted/written page of: Life? or Theatre?: A Song-play gouache on paper; Charlotte Salomon, 1940-42

.

In fact, Salomon’s gesamtkunstwerk is so much more than a journal – it is a meditation on artmaking. Composed of 769 leaves, it is articulated in the style of a light opera or singspiel with prologue, acts and postscripts. Its title, Life? or Theatre? in true Shakespearean fashion, alludes to the ambiguous performative nature of life itself. It is a statement that seems at once absurdist and full of pathos - who can say, the artist seems to imply, what is real and what is not?

For the most part, the film avoids the pitfalls of earlier creators and Salomon is given a distinct artistic identity. The graphic style of the animation is appealing, a hybrid between a retro 2D animation style and German expressionism and it reflects the bold lines and tempestuous colour palette of Salomon’s painting itself. I disagree with reviewers such as John Nugent of Empire, who have described the visual style as “disappointingly conventional.” If the animation had wholeheartedly copied Salomon’s style, there would not be enough separation between the film and the object that inspired it. It is advantageous that the animation style retains some distance from Salomon’s painterly expression; when her paintings are showcased in the film, they shine out like a beacon. Their painterly, feathered textures contrast with the flat, animated planes which surround them. The paintings feel “real” amidst the animation, they wake you up, like the hidden appearance of a photograph in the background of an Aardman Studios Claymation.

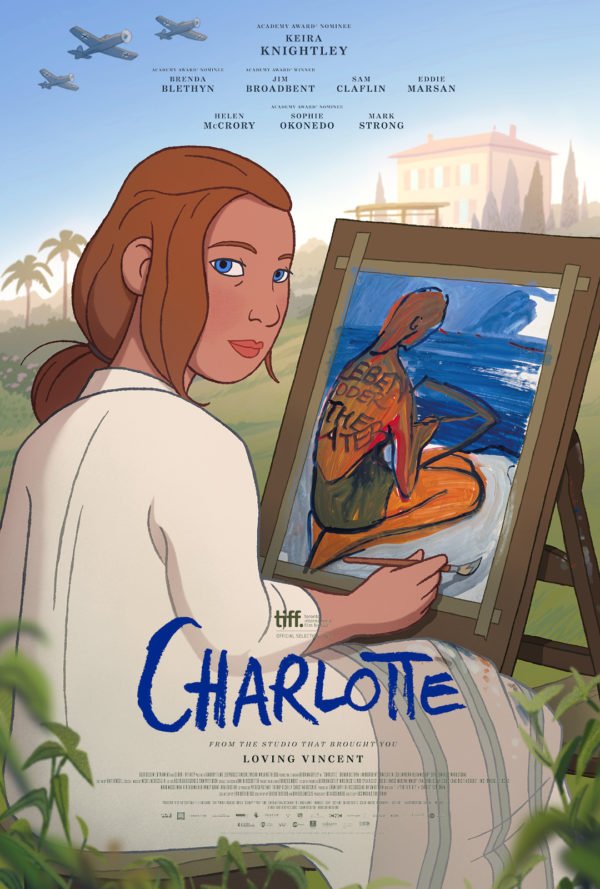

A promotional film poster from Charlotte, 2021, directed by Tahir Rana and Éric Warin.

The filmmakers are ambitious in the statements about the artist. A clear attempt is made to represent Salomon as a modernist, with radically different concerns for figuration than her art school contemporaries. In an early scene in the Academy of Fine Arts, where despite her Jewishness, Salomon has been accepted, a life drawing class plays out. The class, seated in a claustrophobic circle of chairs and easels, is told in pointed terms that the point of the exercise is “precision before all things.” Then, after a moment of silence and the sound of the scratching of pencils on canvas, a melancholic score swells to fill the background; the viewer is left with the strong impression that creative freedom has been proscribed. In contrast to the instruction given, however, Charlotte gets out her paintbrush and… paints. Within moments a figure begins to emerge, delineated in sunshine yellow, colours bleed fluidly into the paper. Returning from her class into the dark night, her older boyfriend Alfred Wolfsohn asks her “did you work well today?” The character replies, with characteristic sardonic humour, “I produced another one of my artistic deformities.”

page of: Life? or Theatre?: A Song-play, gouache on paper; Charlotte Salomon, 1940-42.

The case for Salomon’s modernism is also made through the controversial choice to depict her at the Degenerate Art Exhibition (Berlin 1937) – the infamous show in which luminaries of modern art were exhibited for public derision by the arts wing of the Nazi regime. Although there is no record of whether Charlotte attended this exhibition, as producer Julia Rosenberg remarks in an interview with The Guardian, the filmmakers had to choose to make a stand. “It’s still the most attended art show in the 20th century and, as she was an art student in Berlin, we assumed she would have attended.” It seems a credible wager – Salomon’s work is decidedly avante garde, she surely would not have missed an opportunity to see the art of her contemporaries. Also impressive, is the attention the film pays to the actual text of Salomon’s opus. Salomon makes note, in Life? or Theatre? that her artwork draws inspiration from Michelangelo.

“The following pictures are those which to the author seem the strangest. Without doubt they have their origin in Michelangelo’s Rome series.”

Sure enough, the painting that follows this statement in Life? or Theatre? appears like a hazy, dream-like evocation of the Creation of Adam. God in Salomon’s painting is replaced, however, with an insubstantial purple cloud.

page of: Life? or Theatre?: A Song-pay, gouache on paper; Charlotte Salomon, 1940-42

As if to complement the artist’s insight into her source material, in one early scene Salomon is shown in the Vatican Sistine Chapel; her face is captivated by the renaissance splendour, light and frescoes as she lies down on the floor to absorb the ceiling paintings. Her family are shocked to observe this demonstrative behaviour - but her new friend Ottilie, the woman who will shelter the family in southern France, joins her, showing that they are kindred spirits. In response to Michelangelo, Salomon behaves like the most unselfconscious consumer of contemporary art, lying down like a visitor to an Alexander Calder show at the Tate – a modernist to the core.

The ”true” Charlotte Salomon may or may not have been disinhibited in this way – we will probably never know. However, Charlotte the artist chose to show us, her avatar in Life? or Theatre?, does appear like this. Charlotte Kahn (the name of her artistic alter-ego) is shown to be independent, strident and confident in her abilities. In response to criticism from a fashion drawing teacher, her character declares herself determined to venture out on her own artistically. The caption to the below painting is “Only he who dares can win. Only he who dares can begin”. The leaf depicts the Academy of Fine Arts, where she will enter without parental permission.

The historical Salomon is unknowable. Salomon’s family history contains a history of suicides, murder, and potential abuse, it would be impossible to fully tackle these themes and introduce her artwork in the same piece. In staying close to how the artist represented herself, the filmmakers mostly avoid wading into the murky waters and historical heaviness that await the would-be creator of a documentary.

Charlotte (2021) directed by Tahir Rana and Éric Warin, was released in UK cinemas on the 9th December 2022.