At the Edge of Pictures: John Stezaker, Works 1975–1990, at Luxembourg + Co., London review by William Davie

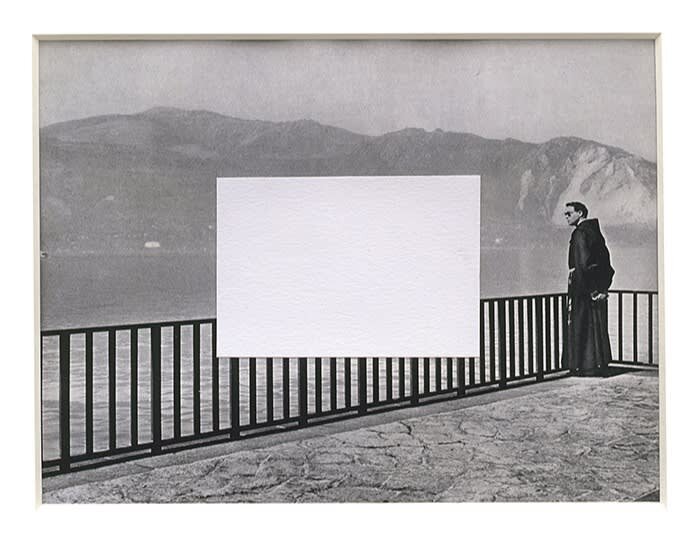

John Stezaker - ‘Untitled (Assisted Readymade)’, 1977, Found image

In the five years prior to Untitled (Assisted readymade), 1977, becoming the artwork we see at the beginning of At the Edge of Pictures: John Stezaker, Works 1975–1990 at Luxembourg + Co., London, Stezaker painstakingly toiled with the question: can this be art?

In 1972 his then-wife had given him a black and white photograph that showed a man playing a piano as a woman watches, resting her head on the lid. The photograph remained on the sheet music holder of their piano in their home. Then, in 1977, Stezaker employed the simple illusory modification he had been wrestling with. He presented it upside down. Immediately this new image reversed the power dynamic between the two.

“I was prioritising what was already there rather than my contribution. So, it became about the consumer. She’s the consumer and through the inversion, the consumer becomes more important than the producer,” Stezaker said of the work.

Examining his early career in At the Edge of Pictures: John Stezaker, Works 1975–1990 this moment seems nothing short of prophetic. The exhibition is concise and agile, but even with a limited amount of material, it doesn’t leave audiences feeling starved for more well-known works. It, along with the fascinating monograph by Dr. Yuval Etgar, exquisitely contextualizes them. I found myself excitedly hurrying back and forth between works as connections and artistic progressions were laid bare.

A surprising revelation is that in order for Stezaker’s work to be truly successful, the viewer must be aware of the violent gesture followed by an act of reparative modification. Cutting, slicing, overlapping, whatever it may be, the physicality of it must be visible. This is because through their positioning Stezaker coaxes viewers towards metaphorical or allegorical readings the two together may stand for yet ultimately denies the two images being synthesized into a seamless new image.

This is demonstrated when studying Care, 1989-90 and Care, 1987-89. In the former, a black and white film still showing two young children, a boy holding a toy and a girl, standing in a room with their parents. Stezaker has cut out the parents and placed underneath a photograph of a cavernous church interior with a vaulted ceiling. Reflexively trying to draw out meaning, the ambiguity oozes ideas of loss and faith while remaining caustically humorous in its visual delivery.

In the latter, a silkscreen using the same image, the void left by the parents is rendered black, while the image from the film still is dark blue. This evokes the sky and silhouette of a cypress tree in van Gogh’s equally hallucinatory Stary Night 1889 as well as his own Father Sky, 1989, seen nearby. But what’s arresting is the impact of scale, almost 2 meters wide compared to 26.5 cm and compression, leaving the work feeling flat and inert in comparison.

In the monograph Richard Prince, who along with other picture generation artists Stezaker was friendly with at the time and spired his interest in silk-screening, recalls walking by a booth at an art fair in Miami and seeing a work from Stezaker’s Love series. The work utilized two copies of the same headshot placed on top of one another, with the eyes cut on the top one so that according to Stezaker, it looked like the protagonist was “blinking.” “It didn’t connect to images but an image to itself,” muses Prince. “Even though we tried to get rid of the seam, perhaps we never really wanted for it to go away altogether. . . we always liked the simplicity it proffered.”

A visual correlation between this silkscreen and his Tabula Rasa series is seen easily. Sharing a motif that has helped define Stezaker’s visual lexicon, these works examine what can be brought out of a juxtaposition between image and absence through omission, in a way the silkscreen Care was not able to achieve.

In Tabula Rasa II, 1983, Stezaker places a rectangle of white card on the centre of a film still showing a man wearing a robe and sunglasses standing by a railing on the edge of a lake, on the right side of the image. Immediately questions are raised, the rest of the visible image is scanned for clues, as the viewer is placed in the position of voyeur. Is the figure looking at this otherworldly shape glowing in front of him, or if it is obscuring a vital part of the image, or if he is even aware of it at all? Critic Michael Bracewell has argued that if read as an allegory, the white space may read as visual representation of the series title and be posited as a “portal within our perception.” In the rest of the series Stezaker deemed the act of cutting out more effective. Opting for rhomboids or trapezoids instead. By using these shapes, which allude to a sense of depth, Stezaker is more successful in illuminating the distinction between film still or postcard and cut, and the way we interpret the relationship between the two. This line of questioning is what sparks the viewer’s imagination, making this series so compelling.

Like the Tabula Rasa series works from the Marriage series, evoke the exploration of literary constraints in Georges Perec’s novels. But it is when overlaying two images that Stezaker’s brilliance is most obvious. Two stellar examples Untitled (Photoroman), 1977 and Mask X, 1982, demonstrate just how studied and honed he was at this manoeuvre. In the former, Stezaker has carefully cropped a woman relaxing on bed talking on a telephone from a Spanish photo roman; a popular form of storytelling similar to comics that uses photographs instead of illustrations that have similar storylines to soap operas. But he upends this by adding a tall, thin cropping of a couple having sex, using it to bifurcate the image of the woman talking on the phone. Immediately, the archetypical scene of domesticity has become something altogether more salacious, fraught with ambiguity and eroticized tension. Its small scale and focused cropping clouding the viewer’s gaze in sense of forbidden spying that vanishes when it is realized that it is your mind putting this together under Stezaker’s guidance.

Conversely, Mask X, triggers an episode of facial pareidolia, a condition whereby a person sees faces in ordinary, inanimate objects. Here, over a black and white publicity headshot of a young actress wearing a sequined dress posing in front of a rope ladder Stezaker positions a colour postcard a figure canoeing along a stony, rural waterway, going underneath a two arched bridge that cuts across the postcard. Because of the position the arches and the central support of the bridge appear to suggest eye sockets and the bridge of the nose of the actress beneath. On further examination, once the humour and absurdity of its suggestion plateaus, like eyes adjusting to the night, the viewer becomes aware that the two images are conjuring a metaphor for within the internal machinations of the woman’s mind. The postcard used in this way “captures exactly what mechanical reproduction did to our way of looking at pictures,” says Etgar. “Where postcards usually make monumental sites into miniatures; film takes mundane things and makes them really huge on the big screen. John’s collages are all about this play of very small and very large.”

It’s power, as in all of his successful works, is like a magician’s sleight of hand. It lies in Stezaker’s ability to condense grand themes and topics into the subtlest of modifications.

John Stezaker - Untitled (Photoroman), 1977, Cut photographic reproductions on paper

John Stezaker - Tabula Rasa II, 1983, White card on film still photograph

John Stezaker - Mask X, 1982, Postcard on film still photograph

John Stezaker - Care, 1987-89, Silkscreen on canvas