Emily Gernild: Aunts and Dolls at Gammel Holtegaard review by Alice Godwin

It is always curious when an artist decides to tie a body of work to a story. It can feel kitschy perhaps, even unnecessary to hide behind tales of another life when a painting might just as brilliantly tell a story of its own. In the case of Danish artist Emily Gernild, known for her dreamy visions of humble objects, flowers, fruit, and vegetation, the history of two women is the entryway into an emotional inner world.

Gernild recalls how she would get the bus as a child to visit her mother’s Aunt Inger and Aunt Eva, who never married and spent their entire lives in a villa in the Copenhagen suburb of Vanløse. Inger was seen as rebellious by the family, and later developed Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and heard voices. Her father hoped that the quiet of the house would provide the peace she needed. In her thirties, Inger was subjected to a lobotomy—a surgery once believed to treat neurological disorders and now viewed as a horrendous mistake by the scientific community—that left her listless and depressed. Eva cared for her sister and their lives were closely entwined.

The eighteenth-century house of Gammel Holtegaard is an inspired setting for a series of paintings largely made in 2023. The exhibition resonates with the story of Inger and Eva, and countless other women whose lives have been contained within the walls of grand homes. The intimate world that Inger and Eva inhabited is the foundation of Gernild’s paintings. Their faces appear through the painterly mist, ghostly and fragile. The ethereal figure of Inger (2023) is Munch-like in its dissonant hues and undulating silhouette, as if a frustrated scream has just been uttered.

Emily Gernild, 'Inger'. 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Gernild’s handling of paint and colour are perfectly suited to the sensuous portrayal of the sisters’ memory, drifting between abstract landscapes and more overt reference to their lives. There is the house itself, the bed where Inger lay and the frosted cakes that their father brought home from his bakery. These flamboyant treats reappear through the show in a nod to historical still life painting and the transience of existence. In Hindbærsnitte (2023) cakes tesselate in geological strata of delectable crimson, purple, and bubble gum pink. Family Dinner (2023) is another feast, where cups, bowls, saucers and an egg seem to abandon the integrity of their form and ooze all over the table. Then there are the dolls that the sisters’ father bought during his business trips. These eerie figures are like infantilized versions of Inger and Eva, kept in their own dolls house in a state of innocence, waiting to be seen and played with.

Emily Gernild, 'Aunts and Dolls'. 2023. Gl. Holtegaard. Photo: David Stjernholm

Relics of Inger and Eva’s lives are found in glass cases—the books they read, the lace gloves they wore. A sink surrounded by bars of soap that hangs on the wall alludes to Inger’s struggle with OCD and the repeated washing of hands. These items liberate the hidden world of the sisters from paint and canvas and gives their story a physicality. The exhibition is also physically divided by curtains, drawn back to evoke a certain theatricality.

The most evocative paintings are those drenched in ambiguity, where the visual signs of the sisters’ world are less clear and Gernild leans more heavily into atmosphere and emotion. In Køkken (2023) a choir of pears anchors a vision of midnight blue to a domestic interior, even as other visible markers dissolve. Elsewhere, a cascade of implements in Napoleonshat (2023) lose their grip on three-dimensional space and float through the painterly ground. These works wonderfully reveal Gernild’s ability to navigate abstraction and figuration and inject an otherworldly presence into her paintings.

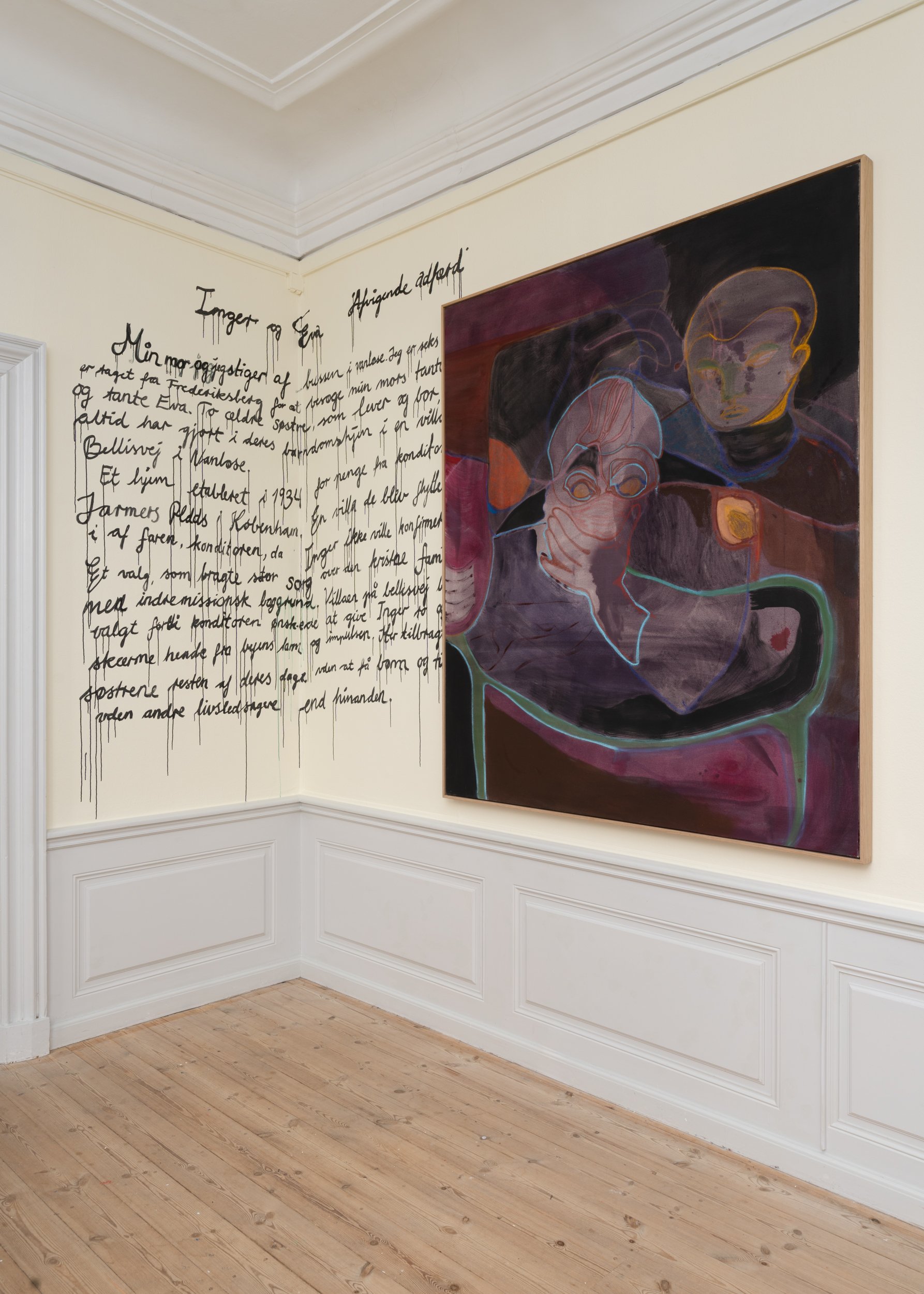

Emily Gernild, 'Aunts and Dolls'. 2023. Gl. Holtegaard. Photo: David Stjernholm

The curious tale of Inger and Eva is a vehicle for marvellous painterly expression. At times paint is lusciously scrawled and at others it is soaked into the canvas, akin to Helen Frankenthaler’s staining technique in post-war America. The lyrical diptych Transformation (2023) particular resonates with Frankenthaler—the right-hand panel is given over to an ocean of blue, while the left contains shapes of earthly brown, as if this is the sea bed below. Gernild constructs her compositions just as she constructs textures and colours. Warm, bodily hues flood the galleries, conjuring a space that is soft and safe. And yet, there is an unmistakable thread of darkness at GL Holtegaard that speaks to the violent treatment of women and their liberation through the twentieth century.

Whether the tale of Inger and Eva is necessary to the enchanted world of Gernild’s paintings or not, the curtains are pulled back to reveal a story of rich, emotional significance. In the final room, Gernild smears a passage of text that drips down the wall; it’s a declaration of intent and the presence of two women who will not be forgotten.

Emily Gernild, 'Aunts and Dolls'. 2023. Gl. Holtegaard. Photo: David Stjernholm